The limits of my language are the limits of my world.

(Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus 5.6)

Desiring is wanting to know. Knowing is not one thing but a multiplicity of ways-of-knowing, each entangling knower and known. I desire iced tea, with a lemon please. I want to know: the taste of light acid and orange-peel bitterness, the tense feeling of ice against teeth, the rush of inner cooling, the calm of impressed memory, of many teas before. Interaction generates embodied resonance between knower and known, forming knowledge as a chord. Each iced tea gives its immediate impression and each impression echoes forward-and-back, becoming coiled as meaning. When we say we “know” we mean the act of knowing, knowing we know by interacting with our knowing, knowing we know by knowing. We know what we know like we know how to ride a bicycle.

There are many modes of knowing. Passively, we feel feelings and think thoughts without always sense-ing or attending to the feeling we feel or thought we think. Passive knowing is an atmosphere, sitting amongst the things we know without focusing on any of them. Yes, I know what it’s like to sit down and have lunch, yes I know what it’s like to lose a few hours on the couch, yes yes, wait, did you say something? Active knowing is attending-to, knowing by interaction. We no longer sit in the haze of knowledge, but reach out, directing our activity towards the object of desire, what we want to know. I know what it’s like to sit in the grass on a Petit Jean summer evening, to feel that grass and that sun and that wind. I know what it’s like to draw the trees, I know what it’s like to read Plato, I know what it’s like to hold my beloved’s hand and sway in the autumn breeze. Each knowing is a melody within a wider symphony, a pattern of notes emanating meaning.

Reflexive knowing, then, is the experience of knowing what we know, or of knowing that we know what we know (maybe even knowing that we know that we know we know). To say “I know” is to interact with oneself as an object of desire, to say “I want to know what I know,” to be known as knower and known. I know how to write a proof in formal logic. I know that I know because I self-reflexively know myself as known knowing: I know that I know how, I know that I know that I can, I think I can I think I can, I know I can. There is likeness to doing, what it’s like to write a proof; but, there is also the likeness of knowing, what it’s like to know that I know I can write a proof. The proof for knowing is not writing the proof but knowing that I could, the proof that proves itself.

The limit of what can be known is the limit of our imagination. The limit of what we can imagine is the limit of our world. In passive knowing, we only know what we presuppose to be the background of the world, the residue or excess of our attention. I cannot imagine that the world I sit in is illusory, that I am just a brain in a vat, because to do so would require that I imagine something other than what I presuppose as the limits of the world, to imagine that whatever world there is is not the world but outside of it. But there is no outside, the world is the outside. So, do I know I’m not a brain in a vat? Yes, because I know the world and nothing else.

In active knowing, we know only what we can take to know, what we can imagine could be known. Whether known known, known unknown, or unknown unknown (where is the unknown known?), I know that the unknown can be known, even if not by me. Knowing is not to hold a true, justified belief that x but to interact with x, even the imagined x, and so know it. The known is known biblically, like knowing you’re naked. Therefore, for something to be beyond knowing it must not be or be only abyss, not to be unknown but to be nothing. It is the same with reflexive thinking, except that we ourselves are what can be known. I can know that I know insofar as I know I am, knowing I know is knowing I’m known. To be reflexively unknowable, I must not be. Cogito ergo sum, because otherwise I’m dead. Except that the cogito isn’t necessary, only sum ergo sum. Whatever the cogito is supposed to be, it always fades into sum. I know you are, but what am I? I know I know I am.

Know thyself.

(The Temple of Apollo)

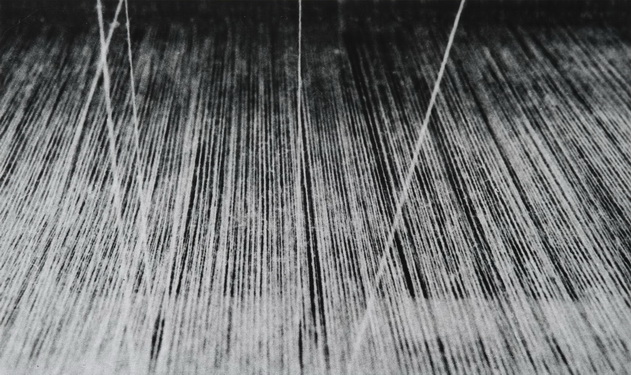

Image: Untitled by Nasreen Mohamedi (1970)