“But my words like silent raindrops fell, and echoed in the wells of silence.” — Simon & Garfunkel, “The Sound of Silence”

Tohu wabohu: without-form, without-substance; cf. aóratos kai akataskeúastos (ἀόρατος καὶ ἀκατασκεύαστος): that which remains invisible and without shape. The no-thing before creation.

There are three kinds of silences —

(1) Silence-as-appearance: The quieting of sense, when impressions dim to form another: the impression of silence or experience of non-sense; the still quiet of a country night, the rustling re-direction of John Cage, the hush between words that creates the conditions for sense.

(2) Silence-in-itself: The quietly un-sensed no-thing that is the precondition for being; apophatic non-sense spoken only in self-negation; cf. Nishida’s basho and absolute nothingness, the self-negated no-thing in which being inheres in the tension of opposites; cf. Tillich’s ground-of-all-being and Pseudo-Dionysius’ negative theology.

(3) Silence-as-presence: The quiet opening of being in the entanglement of placetime, which allows one to encounter unspoken presence in the present-being of the world; this presence is non-sense in resisting sense, no-thing in being caught in the self-negated tension of opposites (the counter-melody of being and nothing that always-already preconditions the flow of placetime), but also a presence in filling the whole of experience with unarticulated feeling, a thisness that permeates time while being unspoken, allowing being-itself to speak.

Why are they playing a cop show at the hospital? Devout, “yes Lord” grandmothers and loved ones finding a distraction in blue lives. (Is philosophy a distraction?) Lifetime cops grunt over hushed chatter. “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name,” the grandmother whispers beneath the Dawn Power Wash commercial. A nurse enters and says to her — did you know she goes by Mabry? No — the nurse leaves. Katie has been back there for thirteen minutes now. I’m writing this in the back of a copy of Bluets (philosophy is a distraction). My emotions feel more alive than the world around me. “Alive.” Hate the word, not a hospital word. The grandmother interjects and paws at me — “did I see you at the library yesterday?” “No.” “Oh, well she looked like you.” She genders me accurately; I don’t think she has full eyesight, but she knows I blur womanly. “Thy Kingdom come, Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.”

It’s been nineteen minutes now. Sometimes the future feels more present than the present. Sometimes this presence is featureless, like a monolith looming over you. Twenty minutes. There’s a vase of flowers in front of me. I think they’re fake; waxy, purple, bouncy, a little too even in coloration. A balloon is tied to it. “Happy Mother’s Day.” Mother’s Day is on Sunday. Mom hasn’t asked me how we’re doing. Mom hasn’t asked me anything. On the table, the magazine About You. About Me? I hope not. Jay Leno grins on a black background above Godfather-type font reading “The Joker.” Are they serious? “I like yellow roses,” the grandmother muses. There are no roses anywhere, but a couple seats over sits a basket of droopy yellow tulips. “Mom is allergic to roses” her companion reminds her. It’s almost been an hour.

Emotions haunt being as an unspoken presence, an illuminating, quiet fullness that is spoken in the expressive unfolding of being-in-time. Emotions bubble up as sensations, but these are not the essence of emotion, only its sensed excess, the uncontainable rupture of affective presence into enfleshed self-communication. The concept of “controlling emotion” is misguided for this reason — it identifies emotion with what is sensed, or with the patterns of thought that accompany sense, or which operate as a sensed sign of emotion’s presence. Controlling these may be prudent, but doing so does not attend to the emotion itself.

Attending to emotion means attuning oneself to the world of unspoken presence that dwells in our being-in-time, the tension that hesychastically expresses itself through our enfleshed activity. Attending to an emotion means allowing it to express itself in being — to reconcile the tension of being and non-being in meaning, not the semantic meaning of terms like ‘happiness’ and ‘sadness’ but the en-worlded meaning of our being-in-time. This is the same whether we attend to joy or attend to suffering. Joy remains tensed in the body even as it escapes to the surface as laughter and smiling and bodily comfort. But this sensed happiness occurs because of the un-tensed expression of what was once suspended in the being and non-being of emotional presence, a possibility inherent in ourself that is then expressed in how we enflesh, entime, and enplace being. Attending to our joy means flowing through that expression, allowing it to become un-tensed in our activity. Likewise, attending to suffering means to express it, to flow through it, to allow it to speak by allowing for being-itself to speak in the silence.

Moments later, I go back to see her. She had a vagal response to her IV, no doubt an ancestral instinct to self-regulate the body when it loses blood. (Weird that nature creates whys) She’s beautiful, sweat darkening her hair against her brow, lightly covered with a thin blanket. She looks like a violet and my mind emanates lavender, the warm, salt-thick lavender of a claw-footed tub, flowers blooming in the steam. Memories press into me, incense dancing delicately through our hair in past images laced with sense. Even in a hospital, the image of her that comes to me is one close and warm, gentle water and the smell of vanilla and brown sugar and sea salt and strawberry. I hold her hand, trying and failing not to betray my anxiety. She reassures me / I should be reassuring her. We nestle together and say goodbye as the nurse pumps medicine into her IV and they wheel her out. The last thing I hear before she goes into surgery is “wheeeeee.” At least she’s vibing. I love her.

I’ve taken an as-needed, warming in the stomach, a deep orange that softens the garish monochrome of the waiting room. The grandmother is no longer here, whisked away by a female relative that frantically moved between work and hospital. I don’t know whether Bluets is taking or giving. When thoughts get caught in the windpipe, maybe receiving someone else’s thoughts is useful. But what is useful about some far off person’s blue-tinted grief? My grief — a grief I can’t locate in space or time, much less the space of reasons — isn’t hued at all. My emotions appear like a massive glass skyscraper, invisible to the eye, an Ozymandian ruin. A brief ellipsis later, a nurse comes out and says everything went well — she’s groggy and waking up, but okay. We’ll know the results later. My heart tries to figure out what to do, speeding up and slowing down at the same time, suspended in the hush of quieting fear. Wheeeee.

The closest analogue to silence-in-itself in Christianity is the apophatic God of mystical theology. Pseudo-Dionysius resists any attempt to define God, to say ‘God is x,’ or involve God in any predication. The apophatics go beyond the cataphatics in resisting not only that God is a being, but also that God is being, or God is. Most orthodox theologians will accept the claim that God is not a being, except in a univocal sense that allows for God’s being to encompass being without being a being in the way that, say, a bee bes. (See Scotus: we can say God is or has properties insofar as we understand that, despite having the same sense, they are magnitudes removed from how that being or property is instantiated in creation. This is a response to Aquinas, who argues that ‘being’ is not univocal between creatures and God, but are only analogues. God ‘is’ or ‘is a being’ in some way similar or analogous to what it means for us to ‘be’ or to be ‘a being,’ but it does not carry the same sense.) However, the apophatics go further in stating that we cannot even ascribe being to God, as God cannot be predicated. There is no essence to God except Godself and no properties belong to God except Godself. The most we can positively say about God is that God Gods, not that God is.

Expression is a hesychasm — an un-ending recitation of enfleshed meaning. The hesychasm in its theological context is the un-ending recitation of the Jesus Prayer, leading to catharsis-theoria-theosis: purification, illumination, and the soul’s union with God. One achieves this union with God through stillness and quiet — the cessation of the individual will for the universal will, the divine will, which speaks through the embodied rhythm of the hesychast. Expression likewise moves from the fully individual sensation of willing, of being-toward, to the communicable, the will that speaks through our ever-mattering togethering. The individual is encountered as silence, but as a silence always on the edge of the expressible, which finds form in singing with the chorus that sits upon the deeper silence. Language symphonizes.

It’s been almost two weeks now. I’m glad I wrote this in the back of Bluets. Thank you, Maggie Nelson, for providing a canvas. A few lines stick with me: “What depression ever felt like a fire? … Then again, perhaps it does feel like a fire — the blue core of it, not the theatrical orange crackling.” (paras. 136, 144) Time is still anxious, though the waves have stilled slightly. In the deep blue, grief crackles but hope alights. I wish I had more to say, more to write, though there’s a reason philosophy is a distraction; it’s therapy for times of pain. And like all forms of language, it always comes up against its limit: silence. Maybe these brief glimpses of life say enough that my not speaking can express itself fully. Wittgenstein was right: “What can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence.”

But, wait, maybe that’s not the right Wittgenstein for the occasion: “What do I know about God and the purpose of life? I know that this world exists. That I am placed in it like my eye in its visual field. That something about it is problematic, which we call its meaning. This meaning does not lie in it but outside of it. That life is the world. That my will penetrates the world. That my will is good or evil. Therefore that good and evil are somehow connected with the meaning of the world. The meaning of life, i.e. the meaning of the world, we can call God. And connect with this the comparison of God to a father. To pray is to think about the meaning of life.” The meaning of life is those you love. To pray is to think about those I love.

Thank you, God, for protecting Katie. Please continue to hold us in inexplicable, unknowing grace, the strength of the divine weakness. Thank you, meaning of life. Thank you, world. Thank you, Katie, for making my life worth living.

Kyrie Eleison.

What is the meaning of life? That was all — a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years. The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark; here was one. – Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

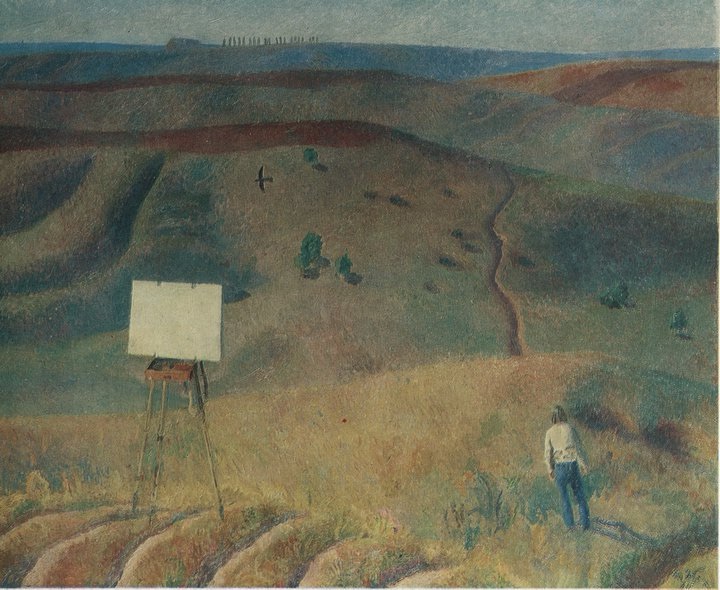

Image: Silence by Tetyana Yablonska (1975)