Dope is death! — Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin, Anarchism & the Black Revolution

Content note: discussion of drug use and death.

Power is a bioregulative force. Capital quantities life by slicing the body into atoms, into sites of manipulation. The body is no longer the enmattered activity of the Unique, but a collection of functional or dysfunctional parts meshed together in a great machine. These parts become sites of exploitation, the transformation of the heat and motion of the human body into virtual accumulation. There is no agent, only surplus, life reduced to excess, socially-necessary labor-time replacing doing. We are zombified animas breathing-in function and breathing-out profit. The ghost of capital replaces species-being with cybernetics and levels spirit into bio-data. Biopolitics eats the soul.

What is a drug? Biochemical manipulation of the bodymind? That is everything, the heat and motion of anima interacting with the world. The universe itself is a drug under this definition. But this is not what “drug” means. A drug serves a particular function in the bioregulation of a social system, the manipulation of the bodymind in a way that markedly enhances or diminishes the functioning of nodes in the machine. SSRIs and fentanyl are both ways to biochemically manipulate our bodymind, producing certain affects in our experience and re-organizing the chemical network that propels our activity. However, in the current social system, SSRIs enhance the functioning of depressed subjects in the system, those whose internal bioregulation produces affects that diminish one’s effective participation in the system. A prole who is too depressed to leave their bed is not participating in the exploitation of surplus value, but acting as a dead-end for that value, not necessarily from the perspective of the subject themselves (for whom the re-organization of their life and social activity may be a preferable salve for their depressed affects), but from the perspective of capital. SSRIs then become interventions by capital to lube the gears of the machine, similar to jump-starting an engine. This does not mean that the subject does not experience benefits from the drug (for my part, I am thankful for Wellbutrin), but that the role of SSRIs within the system of capital is determined by its effect on the system’s functioning, how it allows the proletariat to perform their role as sites of labor-power and attentional consumption. Access to SSRIs are regulated for this reason — doctors, insurers, and pharmacists act as gatekeepers ensuring that the drug is used for its prescribed bioregulative purpose.

Fentanyl, however, diminishes one’s functioning within the system of capital. A prole who is nodding off on fent or orienting their activity towards consuming fent is not efficiently deploying their labor-power for the exploitation of surplus value. Therefore, though fentanyl has many medical uses, its trade is primarily through criminal avenues, the term “drug” being deployed to denote its inefficiency. The user of fent is criminalized in doing so, and their ability to bioregulate their own bodymind is taken away. Clinicians and cops coordinate the enclosure of our own bio-autonomy, allowing us to use drugs that are either prescribed through legitimate means or endorsed by the state, but barring those that lie outside, any form of bioregulation that disrupts or is inefficient for capital accumulation. Notably, however, though the user of fent is criminalized, the pharmaceutical companies that synthesize the drug and who benefit from its illicit trade are not. They retain the institutional authority to bioregulate the proletariat, while the ability of proles to bioregulate ourselves is limited. (This is not to deny the violence of fentanyl, but to point to the inner contradiction of biopower — that the state and capital wield violence and institutional authority to limit the bioregulatory autonomy of the mass of people. Pharma can decay our bodies, but we are not allowed to.)

But is fentanyl fully negative for the system of capital? It certainly diminishes the functioning of the proletariat in their role, and it is identified as such through its criminalization. However, at the same time, it enhances the necroregulation of the machine. While Foucault coined bio-power as the regulation and control of life and life-activities in systems of authority, Achille Mbembe, operating from his position as a racialized and colonized person, coined necropower as the regulation, control, and deployment of death. The role of fentanyl within the system is not to bioregulate the functioning of the proletariat, but to necroregulate the lumpen proletariat and the reserve army of labor — a prole may not use fent because it undermines their exploitation, but the lumpen may because it accelerates it.

The distinction between proles and the lumpen is in their role within capital. Proles reproduce capital by operating as nodes for the exploitation of labor-power and the regulation of attentive consumption, sustaining and accelerating the process of accumulating surplus value, which is at the heart of the self-expansion of capital. However, the lumpen are the excess of the proletariat, who do not inhabit conventional positions within the exploitation of labor-power, but who either do not contribute to that exploitation or who (more commonly) are exploited for surplus value outside of contract or wage-labor. The lumpen include prisoners, the enslaved, the disabled, the institutionalized, the criminalized, the unhoused, and those existing on the edges of capital, typically as part of its internal or external colonies. Many of these groups still serve roles within the accumulation of surplus-value, with enslaved prisoners, workers, and farmhands being exploited for their labor-power without pay, drug dealers synthesizing and distributing the products created by pharmaceutical firms, and criminalized sex workers being exploited through a para-economy of sexual bioregulation. Others, however, are perceived only as excess by capital, with many of the disabled, mad, and unhoused not contributing labor-power, being defunct commodities, or sites of loss rather than gain in surplus value, only producing surplus through the regulation of their bodies in hospitals, institutions, and other sites.

As a whole, the lumpen cannot be bioregulated to perform a proletarian function; instead, capital and the state must deploy necropower to either force the lumpen into sites of exploitation such prisons and institutions, or to diminish or weaken their numbers. This is important for the system of capital not only to squeeze as much surplus value as it can out of human life but because the lumpen are also a site of rebellion. Because of their position at the edges of capital, and the fact that they do not benefit in any way from the reproduction of their position (unlike many proles), the lumpen have the freedom and impetus to act against capital and the state, as demonstrated in riots, prison rebellions, and the organization of gang power into dual power. Many of the lumpen also occupy important positions within capital even as they do not have an incentive to reproduce those positions. Prisoners and the enslaved produce a large portion of the surplus value of capital, criminalized activity produces surplus for firms higher up in the system of distribution, and sex work, disability, and madness act as signifiers to regulate the limits of human embodiment. Because of this, the rebellion of the lumpen is not only a threat because of the potential for acts of anti-capital violence and organization, but because in many cases they can block and slow the reproduction of capital as a whole. For this reason, capital and the state must necroregulate the lumpen for their own survival.

This necroregulation occurs in many ways. Cops and soldiers inflict violence, prisons and institutions create conditions for both social and physical death, the pitting of gangs against one another creates an environment of terror and destruction, and drugs slowly necrotize the social and physical fabric of lumpen communities and shear off the edges of the proletariat into the lumpen. Fentanyl is part of this necroregulation. Though it has medical uses and is produced high in the supply chain, it enters lumpen communities as something that is both incentivized and criminalized. It is not immorality that causes drug dealers to cut other products with fent; they do so for the same reason that Boeing refuses to apply proper safety standards — it is incentivized by the accumulation of capital. What keeps firms intact, whether they be criminalized drug operations or large-scale manufacturers and companies, is that they compete to reproduce the system as a whole by accelerating the process of accumulation. A firm can put morality over profit, but if it does that consistently it will fail, as that which measures and sustains the firm (capital accumulation) requires profit, not only in a small-scale context, but when compared to a wide range of competitors. A dealer can do the right thing and only provide their customers pure heroin, but it will cost more and the customer will receive a smaller, less addictive, high. Whether or not the dealer wants to cut their product with fent, capital wants them to. Doing so increases not only their profits and their rate of repeat customers, but the profits and consumption of the drug market as a whole, including pharmaceutical firms higher up in the supply chain. If they do not do it, there are those who will, and a conscience doesn’t get you far in criminalized economic activity, especially in the colonies.

This means that there is an underlying logic to the distribution of fentanyl that serves a purpose both in the exploitation of surplus value and in the necroregulation of the lumpenproletariat. The fent trade on the ground creates demand for fentanyl higher up, increasing profits for the firms that manufacture it. Likewise, this fent trade both degrades and destroys lumpen communities, killing individuals, splitting up families, and creating conditions under which it is difficult or impossible to organize and rebel. Further, since the trade and its use is criminalized, the state can deploy violence against those same communities that it has incentivized the destruction of. As the super-capitalist, the state both creates the conditions that accelerate the fent trade in the internal and external colonies, and it wields its authority to punish, isolate, kill, and exploit those involved in the trade, many times sending them to sites where their labor-power can be extracted, such as prisons, camps, and institutions. Fent thereby serves the interests of capital even while being condemned by it.

This cycle is repeated again-and-again with new chemicals. Cocaine and heroin are mass produced and legal, until it becomes expedient to simultaneously criminalize them and funnel them into poor and racialized neighborhoods and can be used to fund colonial death squads. Weed cycles through criminalization and legalization depending on if it can be used to stoke white supremacist violence (against Mexican migrants in the 1930s, against Black neighborhoods in the 60s and 70s, etc.) or can contribute to the accumulation of capital (the current legalization boom). Amphetamines are prescribed en masse to neurodivergent children and taken in necrotized forms like methamphetamine by laborers, but these same necrotized forms kill individuals and rend apart communities. The opioid crisis was created by the pharmaceutical industry but those who are punished are desperate and addicted users. In each case, what matters is whether its use enhances or diminishes the accumulation of capital, whether by enhancing the exploitation of surplus value in the proletariat or in suppressing and necroregulating the lumpen. What counts as a “drug” is determined by capital for its own purposes, and the goal of the state’s response is not public health or safety, but the reproduction of the system as a whole.

Fentland is a death camp distributed among the lumpenproletariat.

Junk is an inoculation of death that keeps the body in a condition of emergency. — William S. Burroughs, Junkie

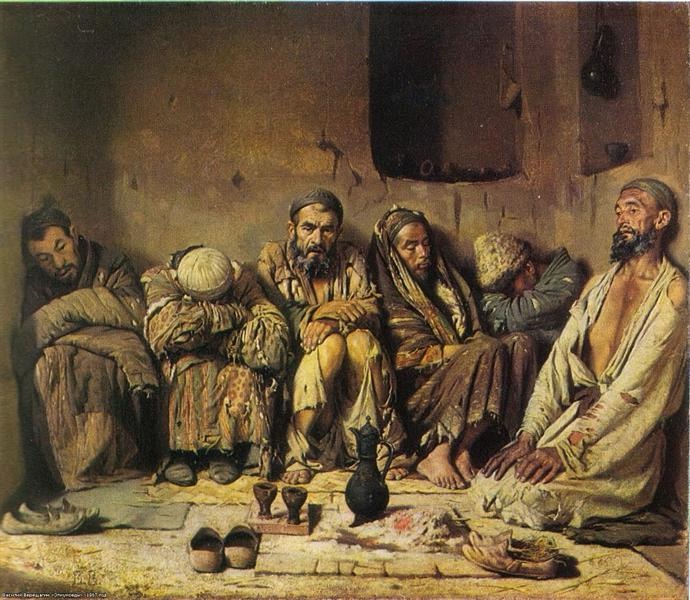

Image: Eaters of Opium by Vasily Vereshchagin (1868)